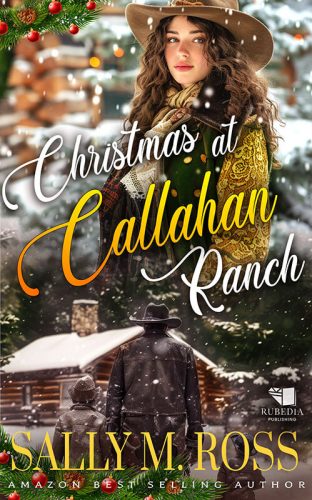

Christmas at Callahan Ranch

Snow’s falling, tempers are hot, and this marriage of convenience is about to get really inconvenient.

Gabriel is a widowed rancher racing against winter and a ruthless banker determined to take his land. With two children counting on him and Christmas fast approaching, desperation pushes him to send for a mail-order bride—not for romance but for survival…

Eve arrives on the snowy frontier with nothing but her courage and hope for a fresh start. A marriage of convenience is her chance to outrun a painful past, but Gabriel’s quiet strength and his children’s longing for tenderness stir feelings she never expected…

“You know what mistletoe means, Gabriel.”

He tips his hat back. “Yeah. Means I’m outta reasons not to kiss you.”

Together, Gabriel and Eve must weather blizzards, rising debts, and small-town corruption. But as Christmas lights their lonely home with unexpected warmth, they’ll discover that the greatest fight isn’t for the ranch—it’s for the love and family they both secretly dream of…

Prologue

Soda Springs, Idaho — 1867

“I can’t do this.”

Gabriel Callahan, widowed father of two, sat at his desk long after the fire in the hearth had burned down to a bed of dull orange embers. The heavy scent of charred pine still clung to the air, mingling with the faint bite of cold that crept in through the chinks in the log walls. He picked up his whiskey glass, drained the last few amber drops, and let the empty vessel rest against his lower lip for a moment before setting it down with a muted clink.

The lamplight guttered, casting uneven shadows across the page before him. He’d started and stopped writing this advertisement more times than he could count. The ink had begun to fade at the edges of old attempts, watermarked by hesitation and damp.

With a slow breath, Gabriel leaned back in his chair, the leather creaking beneath him. His eyes wandered the room, sweeping over the study that had once felt so full of purpose, but was now dim and still, like a relic of another man’s life.

Books lined the rough-hewn shelves along the far wall, spines dulled by time and coal dust. A hunting rifle rested in a cradle above the mantel, its barrel black with age but well-kept, polished out of habit more than need. The flagstone hearth, ringed by soot and ash, still radiated a faint warmth. The firewood stacked beside it smelled of pitch and resin, freshly split that morning, though he’d barely noticed at the time.

His wife’s rocking chair sat undisturbed in the corner, draped in a shawl that still held the faintest trace of lavender sachet, her scent stubbornly clinging through seasons of silence. The ticking of the mantel clock filled the silence with a steady, relentless rhythm, marking time he no longer felt a part of.

The walls, built from thick logs and sealed with mud, bore the scars of harsh winters. The cracks and weathering were obvious, and no amount of caulking could fully mend them. Above his desk, a map of the Idaho Territory curled slightly at the corners, faded by smoke and sun. He remembered tacking it there during the first months after they’d settled, full of plans, full of hope.

Now, the only thing that filled the room was dust and the weight of words left unsaid.

Gabriel turned his attention back to the paper in front of him. He’d written the ad three times already, each version shorter than the last. If he kept this up, he’d be down to one sentence—Need wife to take care of children and house. He scoffed.

It was more difficult than he thought it would be to find the right words. So far, he either sounded desperate or bitter. Truthfully, he was both of those things, but he didn’t want it to come through in his ad. At the same time, he didn’t want to sound too romantic or too cold, either.

This was important. He had to do it right. He needed someone who could help him raise his children and keep the house from falling apart. He needed someone kind and caring. And in return, he’d provide her with a home, food, and security.

He stared at the last words he’d written again:

Thirty-year-old widower with two young children seeks practical, God-fearing woman for marriage. Must be able to cook, keep house, and help with children. Also must be willing to relocate to Idaho Territory.

It felt strange to see it all written out like that. Laura hadn’t even been gone for two years yet. He still reached for her in the night sometimes, forgetting that she wasn’t there.

The accident had happened fast—one moment she was helping him haul feed, and the next she was under the wagon, her ribs crushed and lungs collapsed. The doctor had tried surgery, but it hadn’t worked. It had drained their entire savings and only bought them a few more days.

A soft creak pulled him from the memory, and he turned.

His daughter Joy stood in the doorway, small and barefoot, her nightdress twisted around her legs like she’d tossed and turned in it for hours. At six, she still looked too slight for her age, all thin arms and knobby knees, but there was something in the set of her shoulders that hadn’t been there before. Her copper-brown hair, the same shade as her mother’s, was a tangled halo around her face, and her cheeks were flushed from sleep and crying.

Her eyes, wide and glassy, shimmered in the lamplight. Not long ago, they had been bright things, quick to crinkle with laughter or light up at a story. Now they seemed older, quieter, like they understood too much. She rubbed one with the back of her hand, leaving a damp streak across her cheek.

Gabriel’s heart clenched as he took her in. She’d lost weight since the funeral, nothing drastic, but enough that he noticed how her collarbone showed under the thin cotton of her nightgown, how her ribs fluttered like the wings of a trapped bird when she breathed too fast.

She hadn’t asked for bedtime stories in months. She used to beg for them, used to crawl into her mother’s lap and interrupt the endings with questions. Now, she rarely spoke more than she had to. Grief had made her solemn, cautious. Like every step she took was on a floor that might give way beneath her.

“What is it, honey?”

“I had a bad dream,” she whispered. “I want Ma.”

Gabriel got up and knelt beside her. “Ma’s not here, sweetheart,” he said gently. “She’s in heaven now. Remember?”

Joy nodded, but her lip trembled, betraying the bravado she was trying to hold onto. Without a word, Gabriel rose from his chair, his joints stiff from sitting too long in the cold. He crossed the room in a few quiet steps and bent to lift her, her small arms instinctively wrapping around his neck. Her skin was warm with sleep, damp with the traces of recent tears, and she smelled faintly of chamomile soap and the wool of her blanket. She tucked her head against his shoulder, her breath soft and shallow against his neck.

The wooden floor creaked gently under his weight as he carried her down the narrow hall, the oil lamp in the study casting their long shadows behind them. The children’s room was dark save for the sliver of moonlight slanting in through the warped windowpane. The air held a faint chill, carrying the scent of dry hay and timber from the nearby barn.

He laid Joy back into her bed, careful not to wake Luke in the next one. The quilt was patched and well-worn, a faded calico print his wife had sewn from old dresses and flour sacks. He tucked it gently around Joy’s small frame, smoothing it at the shoulders like her mother used to do.

Luke stirred under his own blanket, a soft sigh, a rustle of limbs, but didn’t wake. His blond curls stuck to his forehead with sleep-sweat, his thumb still resting loosely near his mouth. The silence in the room was deep and fragile, the kind that felt like it might shatter under a single wrong breath.

Gabriel crouched beside the bed for a moment longer, watching Joy’s eyes drift shut. Her lashes fluttered like moth wings, and her breathing slowly evened out, though one hand still clung to the edge of the quilt like a tether.

How could he betray the memory of his late wife by forcing a new ma on them?

He’d rather have a governess, but his funds simply wouldn’t allow for it. He rubbed his face, then turned and walked back to the study.

This was the only option he had. He picked up the ad and read through it once again.

Outside, the first snow had started to fall in a soft, whispering descent that blanketed the earth with quiet purpose. The flakes drifted past the windows in slow spirals, catching the moonlight like ash from a dying fire. They settled on the porch railings, the roof shingles, the fence posts lined like sentries along the edge of the property.

It was only the first of October, but in Southeastern Idaho, a stone’s throw from the Oregon Trail, that meant winter had already begun to test the land’s patience. The air had carried its warning for days, that particular sharpness that bit through wool coats and settled in the lungs like cold smoke. Now, the snow confirmed it. Winter was here, or close enough.

The wind had picked up, too, brushing across the Portneuf River valley in long, low sighs. Gabriel could hear it raking the tall grasses and needling through the pine trees, stirring the brittle branches like bones clacking together. The valley would start to close up soon, trails hidden under ice, rivers swelling with melt and runoff, the passes becoming choked with snowdrifts taller than a wagon wheel. Once that happened, travel would be all but impossible.

So whatever he was going to do, whatever decision he had yet to make, he’d have to do it quickly. Time was slipping away with every flake that touched the ground.

Gabriel sat down again, staring at the ad and willing himself to post it. He hesitated. Sending it felt like he was giving up on something. But not sending it felt even worse.

He folded the paper and slipped it into his coat pocket.

The next morning, Gabriel was up before the sun, rising in the thin, blue dark that came just before first light. The cabin was still and cold, the hearth ashes gray and lifeless. A fine frost rimed the edges of the windows, delicate as lace, and the only sound was the soft, steady breath of his sleeping children in the next room.

He dressed quietly by the dim glow of a stub of candle, pulling on thick woolen socks, worn long johns, and the heavy flannel shirt that still smelled faintly of woodsmoke and sweat. He shrugged into his sheepskin-lined coat, patched at the elbows, and tugged on his boots, the leather stiff from yesterday’s snow. Last came his hat, made of wide-brimmed felt, bent out of shape from years of hard use.

Outside, the cold met him like a slap. It knifed through the gaps in his coat and sank into his bones. His breath came out in clouds, curling into the stillness. The first light was just beginning to rise over the eastern hills, casting a pale silver wash over the land. The snow from the night before had dusted everything, the ground, the barn roof, the split-rail fences, like flour sifted across a rough table. The fields stretched out in a quilt of white and brown, broken by sagebrush and the twisted silhouettes of winter-bare trees.

The Portneuf River was visible in the distance, a dark ribbon snaking through the valley, its banks already crusted with ice. Beyond it, the land rose into foothills thick with pine and aspen, now stripped bare, the mountains beyond capped in white like silent, watching giants.

Gabriel moved fast, not out of urgency but out of necessity. He grabbed the egg basket from the hook by the door and made for the chicken coop. The hens clucked and flapped irritably at the intrusion, their breath puffing in the cold. He worked by feel, reaching under feathered bellies for warm, smooth eggs, dropping them carefully into the basket. The chickens needed feed, too. He scattered cracked corn and seed, watching them peck at the snow-covered ground with single-minded focus.

From there, he moved on to the lean-to where the cattle were kept, some sturdy milk cows and one oxen, their thick coats steaming in the frigid air. The cows lowed as he approached, their voices muffled by the cold. He checked the troughs first; the surface of the water had a thin skin of ice, which he broke with the heel of his glove. Then he hauled hay from the nearby stack, the dry stalks rustling like parchment as he flaked it out into the feed bins.

Then, he ducked into the barn where he was greeted by the familiar scent of hay, manure, and animal musk hanging thick in the air. The lantern hanging from the center beam cast a golden glow over the space. He sat on the old three-legged stool beside Bessie, the oldest of the milk cows, and set about the rhythm of milking, the familiar squeeze and tug, the hiss of milk hitting the pail.

With three milk cows, he used one for his family. The milk from the other two he sold to the general store, along with any extra eggs. It was usually enough to keep them fed and warm throughout the grueling winters. He supplemented his income with the pigs sometimes, as well.

As he worked, his thoughts wandered, always circling the same few questions like a dog worrying a bone. The snow, the passes, the dwindling supplies. Time was closing in on them.

He stared at the milk swirling in the pail, catching flecks of straw and the flicker of lanternlight. He could feel the weight of the day already pressing against him, like the cold itself, quiet, relentless, and full of expectation.

Today, after he fed the horses, he was going to have to ride out and check the fencing in the north pasture. If he waited much longer, they’d be covered in ice and snow, and the ground would be frozen. But he didn’t mind the hard work. It kept his mind off the letter and the hollow space in his chest.

He’d just finished milking and was wiping his hands on a burlap cloth when he heard the unmistakable sound of boots on the floor. Heavy, deliberate steps, soles crunching bits of old straw and grit. Gabriel straightened, his muscles stiff from the cold and crouching, and turned toward the sound.

Alex Monroe stood in the doorway, shoulders hunched slightly against the cold, a folded envelope in one gloved hand. The pale morning light framed him from behind, outlining the brim of his hat and the long, wolf-colored coat dusted with snow. He gave a nod, not formal, but not casual either, the kind of gesture that carried weight between men who’d been through too much together to need words right away.

Alex was Gabriel’s neighbor, yes, their homesteads just a mile apart, but more than that, he was his oldest friend. They’d met nearly ten years back, driving cattle through Montana Territory, both younger, hungrier, and too darn stubborn to die like the others in that wicked snowstorm outside Bozeman. What started as shared hardship became loyalty, and that loyalty had deepened into something steadier than most kin.

He was a tall man, built broad through the chest and shoulders, with the kind of strength that came from years of work, not words. His face was weathered, sun-darkened, creased at the eyes and mouth, but not unkind. His jaw was covered in two days of stubble, and a thin scar ran just under his left cheekbone, a reminder of a barfight in Bannack that neither of them liked to talk about. His eyes were a clear gray-blue, always scanning, always weighing.

“Morning,” Alex said. “Sorry to come by so early.”

Gabriel wiped his hands on a rag. “You’re always welcome. You know that.”

Alex reached into his coat and removed an envelope.

“What’s this?” Gabriel asked.

“It’s from Matthias’s bank. I got one too. Says my loan payment’s past due.”

Gabriel’s stomach dropped. He took the envelope but didn’t open it right away.

“Why didn’t they bring it to me?”

Alex shrugged. “I was at the post office yesterday. Gerry asked me if I’d give it to you.”

Gabriel made a face. It shouldn’t surprise him. Gerry was known for his general laziness.

“They’re tightening up,” Alex continued. “Word is they’re calling in anything late.”

Gabriel nodded, his throat tightening. He’d spent all his savings on Laura’s surgery after the accident. And he’d yet to recover. At the time, the bank was the last thing on his mind.

He forced himself to open the envelope. The words were clear:

Payment overdue. Immediate action required.

He folded the letter and tucked it into his coat. “Thanks for bringing it, Alex.”

Alex gave a nod. “It’s no trouble. Let me know if you need anything.”

“Thanks.”

“Except money,” Alex jested. “I don’t have any of that.”

Despite everything, Gabriel smiled as he watched him walk out of the barn, then he leaned against the stall door. The cold air felt almost painful now. He needed to work. He needed to earn. But first, the children needed breakfast.

Inside, the house was warming up. He stoked the fire in the hearth, then did the same with the oven. He’d taken some bacon from the smokehouse on his way back and dropped it into a skillet while he put the coffee on. He set the table while the bacon cooked, then cracked a few eggs into the skillet, and sliced bread for toast.

Joy came in first, rubbing her eyes with the back of her hand, her hair still a tangled mess of sleep. Luke trailed behind her, clinging to the tail of her nightdress with one hand and dragging a threadbare stuffed rabbit in the other.

At four years old, Luke still had the soft, round features of a child untouched by time. His chubby cheeks were flushed pink from sleep, and he had a small button nose and wide brown eyes that always seemed to be asking silent questions. Where Joy had grown thin and solemn in the wake of their mother’s death, Luke had clung more stubbornly to childhood, though even he had changed in ways Gabriel couldn’t always put a name to.

His hair was a tousled halo of gold, sticking up in odd directions, and his nightshirt hung crooked on his frame, one sleeve twisted halfway up his arm. He moved with the unsteady determination of a boy still learning the edges of his own limbs, his bare feet padding softly across the wooden floor.

He didn’t speak, but his thumb hovered near his mouth, an old habit that had returned since the funeral, and he stuck close to Joy like a shadow.

“Good morning,” Gabriel said, forcing a smile as he spooned eggs onto plates. “Everyone sleep well?”

“Luke was talking in his sleep again,” Joy complained.

“Nuh-uh,” he replied. “I was awake.”

“No, you weren’t,” Joy argued. “Or why would you say that Flossie was chasing you?”

Gabriel chuckled. Flossie was his best sow and was particularly protective where her piglets were concerned. It was absolutely possible—probably even likely—that Luke had a bad dream about Flossie since he was always trying to catch one of her babies.

He set their plates on the table in front of them, poured them some milk, and sat down in his seat. Joy picked at her eggs. Luke ate fast, crumbs falling all over him and on the floor.

Gabriel watched them. They were too young to understand the letter in his coat or the weight of the decision he’d made. They were too young to know what it meant to lose their home. They’d had enough loss in their young lives already. He couldn’t risk them being homeless now, too.

After breakfast, he cleaned up, then sent the kids to dress. He needed someone to watch them while he worked. He couldn’t leave them alone. Not yet. And it was hard on them, making them come with him every day to keep the ranch running. It was hard on him, too.

He pulled the ad from his pocket and read it one last time. The words were clear. Plain. Honest. He folded it back up, slid it into an envelope, and sealed it. They’d go to the post office before lunch.

It wasn’t an ideal solution. It wasn’t even a good plan. But it was a step. And right now, it was all he had.

He grabbed the bucket of leftovers from the kitchen, then bundled the children in their warmest coats and herded them out the front door.

“What are we doing first?” Joy asked.

“We need to go feed the hogs first,” he replied. “Then, the horses. So, you two come help me hitch the wagon.”

He watched as they tore off toward the barn. He’d found that by giving them a few light chores—folding laundry, sweeping the floor, helping him with light tasks in the yard—he could watch them more easily and keep them out of mischief.

“That doesn’t go there,” Joy told Luke. “You’re going to break it.”

“Nuh-uh,” Luke replied, trying to force a leather strap into the wrong buckle.

“Here,” Gabriel said, taking the strap from him. “I’ll do that. You go pick out which horses we’re going to use today while Joy starts filling the feed buckets.”

“I want Rowdy,” Luke announced.

“Rowdy’s a mule,” Gabriel replied. “I want two horses.”

Joy walked over and gathered the feed buckets, carrying them back over to the feed barrels and scooping out enough grain for their dozen or so horses. One of them, Laila, was about to give birth. He’d have to bring her into the barn soon.

After hitching the two horses that Luke had picked out—Rainbow and Apache—he loaded the children into the back with the feed and led the horses away from the barn. The snow had thickened, covering the ground now in a thin crust.

“Pa, can I chop some wood later?” Joy asked as they passed the dwindling wood pile.

“I don’t think so,” he chuckled. “But I’ll let you put some on the fire later.”

He held the reins loosely in his hands as they headed to the pasture. Soon enough, they came to the gate.

“Joy, you and Luke go open the gate,” he said as he pulled the team to a stop.

He watched as they both jumped down from the wagon and ran to the gate. Joy unlocked it while Luke climbed on and waited.

“Yee-haw,” he shouted as the fence swung open.

Gabriel chuckled as he drove the team through the open gate. He loved his kids. Sure, he was tired, run-down, out of patience, and money. But they were the only light in his life right now. In fact, if it weren’t for them, he was pretty sure he wouldn’t have cracked a smile in the past two years.

He waited while Luke and Joy closed the gate. His mind kept circling back to the envelope in his coat. He wondered what kind of woman might answer. He wondered if she’d be kind to Joy and patient with Luke. He wondered if she’d hate the cold, or the quiet, or the way the wind never stopped blowing here.

He really didn’t want a stranger living in his house with him and his children. But he couldn’t very well marry and move his wife into one of the outbuildings. He hoped to find someone with a good personality who could become familiar quickly. Someone who wouldn’t flinch at hard work.

He didn’t want much.

By early afternoon, he was back at home, brushing snow off his coat. The children went straight to the fire, trying to warm up. Gabriel took off his coat and hat and hung them by the door. Then, he went to the kitchen and pulled out some cheese for lunch.

While he sliced the bread, Joy read aloud from a picture book to her brother. She couldn’t really read very well. He suspected she had memorized the words from all the times he’d read it to her.

Luke didn’t seem to care. He curled up beside her, listening intently. Gabriel took the rest of the bread from the pantry and started slicing. He felt like he’d just made this loaf, and they were already almost out. He’d have to make some more tonight.

He’d add that to his growing list of things he needed to do.

He continued slicing, thinking about the way Alex had looked at him when he’d handed him the envelope earlier.

Once his bride showed up on the town’s doorstep, there’d be no keeping the cat in the bag. But it couldn’t be helped. Because the children needed more than what he could give alone.

Because the house needed more than just half-done laundry and bacon and eggs for every meal. Because, unfortunately, that was the only thing he knew how to cook.

And because sometimes, even in the dark of night and the icy cold of winter, you had to believe something better might come.

Next chapter ...

You just read the first chapters of "Christmas at Callahan Ranch"!

Are you ready, for an emotional roller-coaster, filled with drama and excitement?

If yes, just click this button to find how the story ends!

I hate waiting. Then I forget I want to read it.

I admit I understand! That’s why, if you’re subscribed to my mailing list, you can get reminders for free when the book is out! You can follow this link: https://sallymross.com/novella (subscription + novella included)💗

This is going to be another winner from you. Very much looking forward to the rest of the story. Thank you for the opportunity to read this.

Thank you for reading my stories, Donna, you’re the best!😍

Looking forward to reading this story!

I hope it kept you good company during Christmas!🥰

The preview really wants to make me read the book. I could relate to Gabriel as we live on a farm.

That sounds lovely, Barbara!🤠