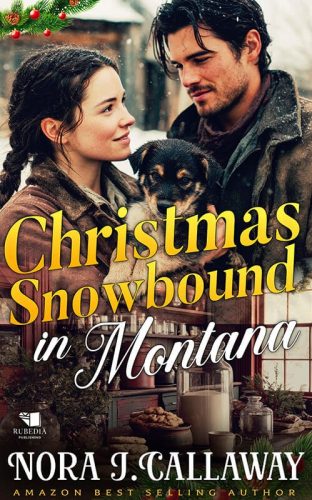

Christmas Snowbound in Montana

“I lost everything,” she whispered into the quiet cabin.

“You didn’t lose me,” he said.

Clara McKenna never expected to seek shelter at the ranch of the man who once broke her heart. When a brutal winter storm collapses her roof, she has no choice but to turn to Luke Callahan, the only rancher close enough to help—and the last man she ever wanted to face again.

Luke Callahan built his life on duty and the walls he erected after losing Clara. When she appears on his doorstep in the middle of a blizzard, shaken and nearly homeless, old feelings break through the ice he’s carried for years.

As Christmas approaches and a ruthless gang circles closer, Clara and Luke must choose whether to trust each other once more. Will the warmth of Christmas bring them back together, or will fear and pride keep their hearts snowbound forever?

Snow falls soft on broken hearts,

a winter sky where old wounds shine.

But in the warmth of Christmas light,

their love returns like a promised sign.

Prologue

Montana Territory, November 1881

The family cemetery was sheltered by a small grove of cottonwoods. Otherwise, it would have disappeared like everything else beneath the sparkling snowdrifts that swept across the Montana plains. It wouldn’t have mattered if it had vanished. After ten years of making the same trek every few months, Clara McKenna and her mount still would have found their way without hesitation.

“Whoa, Charlie.”

As the rangy quarter horse halted beneath the thin blue shadows of the trees, Clara kicked her boots free of the stirrups and swung out of the saddle. She tipped her head forward so that her hat shaded her eyes and squinted over the scarf that covered her mouth and nose. Powdery snow dragged at her legs, pressing cold through layers of wool as she trudged toward the three gray stones barely visible above the swirls and mounds of white.

Bending down, she brushed her mitten gently over the first stone, uncovering the simply carved memorial on its face.

Laurell M. McKenna

Beloved of Her Family

1840 – 1865

Weariness more than sadness wrapped its weight around Clara’s shoulders as she gazed at the grave. She had been only ten years old when her mother had died. If it hadn’t been for the fact that Clara had matured to look almost just like her—with the same coffee-colored hair, hazel eyes, and pointed features—she likely would have forgotten what her mother looked like.

“And now I’m a year older now than you had a chance to be.”

Clara swallowed as her mouth filled with the familiar, bitter taste of regret over all the might-have-beens. How would the past sixteen years of her life have been different had her mother been there to guide her through them? And what would Laurell McKenna think of the woman her daughter had become?

She lifted her chin as the question formed. Most women old enough to be her mother eyed her with thinly veiled distrust and judgement. If she was their daughter, their expressions seemed to say, they would be having words about the clothes she wore and the company she kept. They would have raised her to know better.

Clara had long ago learned not to care what these women thought of her. She wasn’t their daughter, so why should she? “I refuse to believe you’d be disappointed in me,” she whispered fiercely over her mother’s grave.

Turning to the next stone, she brushed it clear with one hasty motion.

Davie J. McKenna

In Jesus’ Arms

1865

At ten years old, Clara had always wanted a little brother. But when he had come, he had lasted less than a day. And when he had gone, he had taken their mother with him. It struck Clara afresh how quickly the beautiful things of life could appear, and how just as quickly they could vanish.

It wasn’t until she turned to her father’s grave, the freshest of the three, that tears welled in her eyes. They immediately froze on her lashes, and she lifted an impatient mitten to dash the ice crystals away.

Joshua E. McKenna

Father and Friend

1835 – 1871

Papa, I still miss you. So much.

Even now, ten years after his death, she could still call up the image of his face, creased with smile lines and full of warmth and steadiness. There had never been another man like her father. And there never would be.

Clara gazed at her father’s grave for a long moment. Once again, she was conscious of feeling more tired than sad. She was physically tired; ranch chores in three feet of snow would do that to a body. But she was also emotionally tired. Tired of mourning, of missing, of carrying everything alone.

“Happy birthday to me, I guess,” she finally muttered aloud. A ragged laugh caught in her throat as she whisked away another rime of frozen tears with angry efficiency. “Maybe it’s time to find a new way to celebrate.”

Pressing a kiss to the frosty fingers of her mitten, she touched it to each of the three stones in turn. Then, abruptly, she straightened and whirled away. She took a deep breath of the freezing air as she stalked back to her waiting horse. It burned her lungs, replacing the uneasy ache in her chest with a simpler physical pain she welcomed.

There were only a few days each year that she allowed herself to probe the broken edges of her heart and memories. But she found the ice she kept packed around her wounds thawed more slowly than it used to and hardened back into its protective shell with more alacrity.

Perhaps what the cowboys said behind her back was coming true at last. Perhaps the impassive façade she had donned upon her father’s death, in an effort to be strong and keep his beloved ranch afloat, had so settled into her that it had become who she truly was.

I don’t care. Clara squared her shoulders and clenched her teeth. I don’t care. I’ve done what I have to do, and I am who I am. There’s no turning back time.

She grabbed Charlie’s saddle horn and shoved her boot back into the stirrup, swinging up with a swift, practiced motion.

“Let’s go home, boy,” she sighed.

As they turned, her gaze caught on a dark figure, moving along the horizon. It was a man on horseback, trotting steadily along a parallel course to the one she was about to take.

Her stomach knotted and her shoulders tensed.

Darn Luke Callahan.

“Can you never stay on your own property,” she growled into her frozen scarf.

As if he had heard her, the man’s head turned. He was too far away to see his face, but she knew at once that he had seen her. She could feel the intensity of his gaze even from here.

She had an almost irresistible urge to make a rude gesture, but to do so, she would have to remove a mitten and risk her fingers getting frostbite. After staring angrily back at him for a few seconds, she settled for an ironic salute, ending with her entire hand pointing him back the way he had come.

“Get off my property,” she gritted from between her teeth. “And stop loitering along the edge of it like a hungry coyote. I know you want it, but you’re not getting it. So, scat.”

Silhouetted against the sky half a mile away, Luke Callahan lifted a hand and touched his hat brim. Then, he turned and rode out of sight.

Finally.

Cursing the gnarl that lingered in her stomach, Clara nudged Charlie into a walk. After a moment, he broke into a trot of his own accord. Snow flew from under his hooves and whisked across the sprawled plain. The wind had picked up since her ride out. It shoved a cold fist against her coat and whipped dark strands of hair across her eyes. Clara shook them away, casting her gaze toward the sky.

Clouds scuttled across the blue, like sheep ahead of a sheep dog. Their bellies were dark gray. Even as she peered upward, silver flakes begin to spin down. They touched her cheeks like tiny kisses and made her blink as they landed in her eyes.

Her horse reached the top of a small rise and the McKenna ranch buildings came into view, huddled among a smattering of gigantic ponderosas. Immediately, Clara was aware that something was wrong— dreadfully, stomach-sickeningly wrong. But it took a long, horrifying moment for the problem to crystallize into coherent thought.

Where is my house?

Where it should have been, there were green branches, awkward and uncanny, waving toward the sky. They were vertical instead of horizontal, splintered through with jagged red wood, walls and beams. A mass of chaos stood where the tidy little McKenna ranch house once had. Above it was a hole among the towering pines: gray sky whipped with shimmering snowflakes.

Shock, confusion, and disbelief made Clara feel as if she was spinning out of control. For a moment, she thought she might vomit. Charlie cantered down the last slope of the hill, past the barn, to within a few feet of the catastrophe. He pulled up with a snort as Clara’s hands convulsed around the reins.

Her house had been completely shattered by the enormous trunk and branches of the tree that had fallen directly through its middle. She could see pots and pans among the snow-laden greenery, the heap of quilts that covered her bed. Giant splinters of timber and wooden shingles had flown in every direction at the impact, burying themselves in the snow up to a hundred feet away.

Clara’s two hired hands stood gazing at the destruction. They turned as her horse drew up beside them. Danny, the younger and bonier of the two, lifted a hand to his push back his hat. It shook slightly.

“We don’t know what happened, Miss Clara,” he stuttered, his face long with astonishment. “We just heard the crash and come out to see.”

“I reckon it was the snow,” Oliver said. He was a bit older, with graying hair and a slight pot belly. “All that weight. And too much freezing. Cracked the old girl up from the inside. It happens.”

“I didn’t hear it,” Clara said faintly. It wasn’t what she meant to say. At least, she didn’t think it was. She still felt too stunned to even know what she was saying or thinking. It seemed completely impossible that she was sitting here, staring at a splintered pile that had once been her home.

Oliver tilted his grizzled face to the snow, which was falling thicker and faster by the second.

“Reckon that’s cause the wind was behind you,” he said. “Blew the sound away.”

There was movement among the shattered fragments of house and tree. A large red squirrel emerged from beneath the greenery and crept along the trunk of the pine. He tottered to the end of a branch and up a broken beam of what had once been the kitchen ceiling. Then he gathered himself, leapt into the air, and landed on the low-hanging branch of another nearby pine. Scrambling upward, he disappeared.

Clara’s gaze fell back to the house, her eyes catching once again on the bright red and gold gingham of her quilt, squashed beneath a branch oozing sap and heaped with ruffed snow. Her heart pounded in her ears as reality sank in. Unlike the squirrel, she couldn’t just climb from one home to another.

My house is gone.

“Where am I going to sleep?” she murmured.

“The bunkhouse?” Danny suggested. She looked at him, blinking.

My house is…

He flushed. “We’ll move out, o’course,” he added hurriedly.

“To where?”

“The barn.” Oliver straightened his shoulders as she turned to look at him, making his belly pop out a bit more over his belt. “We’ll sleep in the barn,” he repeated gallantly.

Gone.

As the shock rolled through her one last time, she accepted it. Just as she had when she her mother and baby brother had died on the same day. Just as she had when her beloved father had left her alone to run the ranch at only seventeen. Just as she had… oh, so many times in so many ways.

With her acceptance came the urge to put her head down against Charlie’s neck and sob, but Clara held herself in check. Long practice stiffened her spine and sharpened her awareness. She noticed, at last, that neither Danny nor Oliver were dressed for the cold. They had run from the bunkhouse hurriedly, throwing on little more than their coats and Stetsons.

“You can’t sleep in the barn,” she said. “Not in this weather.”

“But Miss Clara, we can’t all sleep in the bunkhouse,” Ollie protested. “It wouldn’t be right, and folks…”

Clara shook her head before the older man could continue to lecture her about something about which he knew absolutely nothing. She knew she couldn’t sleep in the bunkhouse. It was tiny, more a cottage than anything, and had housed a string of none-too-sanitary ranch hands over the past years. The last time she had ventured to poke her nose in there, she’d regretted it for the rest of the week.

“Never mind.” Her voice came out too soft, almost whispery. She cleared her throat and started again, stronger. “Never mind. You two go bundle up. The animals still need caring for, and we’d best do it before this storm gets any worse. Don’t worry about me. I’ll… I’ll figure something out.”

Chapter One

“All good and buttoned up?” Luke asked as he met Hank halfway between the house and the barn. The air was a flurry of swirling flakes, falling so thick he could barely see his foreman’s face in the gathering dusk.

“Yup. It can snow all night if it wants to. The livestock are under shelter, there’s plenty of feed to go around, and the buildings are all holding their own.” Hank grinned, tipping his head so that the snow fluttered around the brim of his hat and sprinkled against his lean, sun-brown face. “You can rest easy ‘til morning, boss.”

“Yeah, well, we’ll see. We’ve already had a record amount of snow this season so far, don’t you think?” Luke grimaced, glancing at the heavy gray horizon. “I reckon some ranchers might have more to worry about than we do.”

“You’re thinking about Clara McKenna.”

It wasn’t a question. Hank knew him well— maybe too well.

Luke rolled his shoulders, fighting the crick in his neck.

“The woman doesn’t know what’s good for her is all,” he muttered finally. “When was the last time you suppose she had someone climb up and check the roofs of her buildings? The fellow she’s got running things over there, Oliver? No way that lazy bones is going to do something like that without being told to. That place is going to fall down around her one of these days, and that’s a fact.”

He stopped abruptly, noticing how animated his voice had grown. Heat flushed his face despite the bite of the wind. It was unlike him to rattle on like that. But Hank knew the old McKenna ranch was a sore spot for him.

The foreman’s expression didn’t change. “You don’t reckon her pa taught her to take care of things like that?” he asked diffidently.

“She was seventeen when he died,” Luke snapped “How much could he have had a chance to teach her?”

“Oh,” Hank said, tilting his head.

“’Oh’, what?”

“It was this time of year, wasn’t it?” Hank asked quietly. “I remember you saying, the first time you had me ask her about selling the place to you, to wait until after the New Year because she would be feeling too sentimental leading up to Christmas.”

“Everyone feels sentimental leading up to Christmas.” Luke glanced away from his hired hand, shoving his mittened hands into the deep pockets of his coat to hide the emotion that managed to prick him, no matter how many years had passed. “And everyone gets a little desperate after New Years,” he added halfheartedly.

“Hmm. If you say so,” Hank said.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Luke demanded, yanking his attention back.

“Nothing much, I reckon.”

“Spit it out,” Luke insisted. He and Hank hardly ever had disagreements, and it was making him feel like a dog having its fur rubbed the wrong way that they were having some kind of argument now.

He especially didn’t like that he wasn’t even sure what they were arguing about or why.

“You worry about that woman. All year long, I reckon, but especially as it starts to get cold.” Hank chuckled, warming to his topic, shaking his head with a delighted expression, like he should have known all along. “I’m starting to suspect that’s the only reason you ever wanted to buy her land. Them big hazel eyes and good figure. Even if she is always dressed like a man and working like one too. There’s a lot of men around these parts that don’t mind that at all.”

“Whether they do or not means nothing to me,” Luke said icily. “Never mind.” He turned, ready to get as far away from this conversation as possible. At the last minute, he remembered his manners and half turned back toward the foreman, asking gruffly, “You wanna come in for a coffee before you head out?”

Hank’s smile flashed. His gray eyes seemed to have taken on an extra sparkle over the last few minutes of their conversation. “Nah, that’s okay, boss,” he said easily. “I’ll just join the boys in the bunkhouse for a while before I head to my cabin. Wyatt shot himself a few quail today, and they’re having a feast out there.”

“All right, then.” Luke managed a stiff nod. “Don’t stay too long. This storm’s only going to get worse, and then even getting to the cabin will be too dangerous.”

“Now, don’t you go worrying about me too,” Hank teased. “I’m a big strong man. I can take care of myself. Clara McKenna, on the other hand—”

Luke didn’t stay to let him finish. He stomped up the stairs to the ranch house door as Hank’s satisfied laughter sifted through the snow after him. Opening the door, he stepped into the house and closed it firmly behind him.

He was enveloped by stiflingly warm air, scented with pine, cinnamon, apples, and flaky pastry. Laughter sounded from the living room, the hearty chuckle of his mother, Martha, mingled with Lily’s spontaneous giggles.

Luke fumbled with his thick, wool scarf and the buttons on his coat. The heat was so thick and dry after the crisp damp of the outside world, he had the sense he would smother if he didn’t get out of his layers right away. Already, the ice and snow were melting from his boots into a puddle on the hardwood floor. Dumping his wraps on the wall hook by the door, he wrestled one foot out of a boot, stumbled slightly off-balance, and stepped right in the cold water.

“Darn it,” he mumbled, exasperation flooding.

“Luke, is that you?” his mother called.

“Pa!” Lily squealed. A second later, the six-year-old spun around the corner, her arms flung wide and her brown braids streaming behind her. Luke barely got his other boot off in time to straighten up and meet her hug with open arms of his own.

He wrapped his arms around her and lifted her off the ground. Some of the tension and tiredness that had seeped into his bones during the long hours of cold outdoor work ebbed away as he felt her heart beating quickly against his and breathed in the sugar and soap scent of her.

“Pa,” she babbled in his ear, “you’ve got to come and see. The tree is looking bee-a-utiful! And we made little pies with stars on them! And it’s snowing!”

“That I’ve already seen,” Luke replied wryly. As Lily squirmed in his arms, he set her back on the floor and followed her eager scamper back toward the center of the house. The heat and fragrance grew stronger as they stepped into the joint living area and kitchen.

Sure enough, the Christmas tree he had been talked into cutting down and dragging into the house that morning stood tall and bushy beside the stairs, garlanded with ribbons and pinecones. Silver and glass ornaments that had decorated every tree since his childhood sparkled and swayed on the branches. His mother had told him they came from “the Old Country”, where their ancestors had been silver smiths, glassblowers, and stable-keepers, the ancestral livelihood to which Luke gravitated.

Martha stood next to the tree, stretching onto her tiptoes to hang a final ornament near the top.

“Oh, goodness,” she exclaimed suddenly, losing her balance. Her arms flailed outwards as she tottered and windmilled them in an attempt to regain her equilibrium.

Luke crossed the floor in two long strides, catching her with an arm across her back before she could tip all the way over.

“My lands!” she laughed breathlessly. “I nearly went over that time! Thank you, darling.”

As he set her back on her feet and she patted his arm, Luke found himself noticing the smile lines that creased her cheeks, the way her apron strained around her middle, and the gray hair that sprang from her bun. For a moment, he was intensely conscious of reality clashing with the childhood memories he had just been reliving, when his mother had been young and slim and light on her feet.

It was an incongruent feeling that doubled his prickly humor. This was one of the things he almost hated about Christmas, he thought, the way it stayed the same while the people one shared it with kept changing. Or even fading away entirely.

A solitary figure on horseback drifted across his mind’s eye. He blinked it away.

“Are you okay?” he asked, stepping back.

“Just stretched a little higher than I should have,” Martha chuckled. “Lily’s had me rushing around all afternoon, getting this tree and some special goodies fixed. I suppose I’m a little light-headed and ready for dinner is all.”

“You’re probably light-headed because you’ve got it so hot in here.” He turned to the fireplace, which was roaring with logs he’d spent the better part of the last few months chopping down to size. “Are you trying to cook us as well as whatever you’ve got going for supper?”

Lily giggled, skipping up beside him to grab at his hand. “You’ll like what we’ve got for supper,” she assured him as he turned his attention to her.

“Well, I don’t like to hear that you’ve been making your grandma do more than she’s able,” he scolded lightly.

Lily’s face fell as her eyes flickered over his expression.

“Oh, now, don’t go making it sound like I’m an old woman before my time,” Martha protested. “I am sorry about the fire,” she added. “When the snow and wind started, it just got to feeling chilly all around the edges of the house. I thought we’d warm it up for you to come into and for us to sleep tonight.”

“I’m sure it will be plenty warm for us to sleep,” Luke grumbled. However, he attempted to soften his tone with a half-smile in Lily’s and Martha’s direction. “That’s why we built the house around the chimney after all.”

“So it is.” Martha smiled down at Lily and clapped her hands. “Come now, hon, help me lay the table. I’m sure your pa is tired and hungry from working all day. We mustn’t make him wait any longer for our foolishness.”

“It’s not foolishness,” Lily protested as she scampered after her grandmother. “It’s Christmas!”

Well, some of it had been foolishness, Luke thought. He strode to the fireplace and grabbed a poker to roll some of the logs off to the side to lessen the blaze.

But his mother’s words made him wince inwardly. Another memory clamored, one that had been laid down hard in his mind through many repetitions. His mother’s voice: We mustn’t keep your pa waiting. We mustn’t antagonize your pa. Your pa won’t like that…

He turned to watch Martha and Lily scurry about the kitchen, gathering up the napkins and silverware for the raw oak table that sat in its center. He could still sense the irritation that he’d come in wearing like an extra layer of winter clothing, and he found himself examining it in a new light.

Was he becoming his father?

The thought was far more chilling than the blizzard outside.

As if his comparison was an invitation to prove itself, the wind outside the windows suddenly gusted, rattling the glass in its frames and howling around the eaves. Luke went to the closest one and cupped his hand against the glass. All he could see was the rushing white race of snowflakes clogging the darkness.

He hoped that Hank would play it safe and just stay over in the bunkhouse with the other hands for the night. No one should be out in this storm. That would be foolishness.

Turning back to the warm, glowing inside of the house, Luke forced himself to relax, to release the taut, unhappy feeling that had filled him since he’d seen Clara McKenna riding back from her family’s graves. That was where his mood had turned, and he knew it.

How was it that even after all these years, he could never seem to encounter her as a normal person? Every time they ran into each other, or even when he just spotted her from a distance, he came away with a thorn in his side.

Hank was right. Luke tried to disguise it as complaint, even to himself, but he worried about her. Even today, watching her ride through the snow with the confidence and ease of a woman who had practically been born on horseback, he had felt the urge to go to her, to help her.

Help her with what?

Next chapter ...

You just read the first chapters of "Christmas Snowbound in Montana"!

Are you ready, for an emotional roller-coaster, filled with drama and excitement?

If yes, just click this button to find how the story ends!

Like getting the first bite

Of the most delicious treat, then it was taken away and you have to wait!

Now I will be antsy until I get it!! Thank you. You always it it out of the ballpark. 🥰

Now, that’s the best image to describe this situation!!! It’s always worth it, I promise!😍

Looks to be another great Western! Looking forward to reading the whole book.

Hope you enjoyed it, Barbara!💌