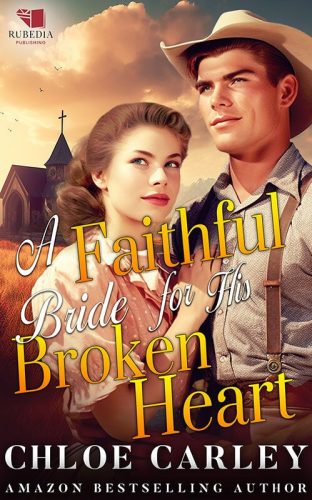

A Faithful Bride for His Broken Heart

While looking for refuge in the arms of a stranger, she’ll discover that God works in mysterious ways, unfolding unexpected blessings.

Lena escapes the clutches of her abusive uncle, armed only with her mother’s cherished Bible. Determined and resilient, she seeks a new beginning through a daring act—answering a mail-order bride ad…

Sam, once a man of unwavering faith, now finds himself shattered by the weight of loss and neglect. Reluctantly seeking help to save his ranch, he finds himself drawn to Lena, her smile, a reminder of happier times…

And as their paths intertwine, a sinister force makes its appearance—a ruthless banker intent on seizing their land and tearing apart their fragile happiness.

Prologue

Goshen, Nebraska

August, 1877

Lena Tass closed Mama’s Bible and tucked it under her pillow. Before she fell asleep at night, she liked to go through the Bible and find the words that she recognized. Her teacher told her it was a way of making sure that she knew the words she was learning. Lena was nine years old and had just started her schooling. There were no teachers in Goshen, Nebraska, or hadn’t been until old Mrs. Olafsen had come to town to live with her son and his family, the nearest neighbors to the Tass family. Lena was learning to read, something Mama and Papa couldn’t do but wanted her to know how to do.

Lena liked Mrs. Olafsen very much. “You are a smart girl, Lena, and you will know how to read and write. I will make sure of this. You will see how much there is to learn. But first,” Mrs. Olafsen had held up the Bible in her hand, “first you learn this—God’s Word. Itis the way to paradise.”

Lena could now read all the words from verse eight of Psalm 34: O taste and see that the Lord is good: blessed is the man that trusteth in him.

She told Mrs. Olafsen that, even though she could see the words, she did not understand how anyone could taste them. Mrs. Olafsen never scoffed or scolded at questions. She had placed her hand over her heart. “Reading and learning are the first thing. Then comes understanding of the meaning. Sometimes, we are hungry, yes? We are cold, yes? We are afraid, yes? Then we come to know God inside, in the heart and in the belly. You will understand when you are old enough.”

There were many things that Lena did not understand. She knew how to read them, but she wasn’t sure what they meant.

Lena lifted her head up to listen—finally, quiet. The low hum of voices coming from the kitchen had ended. Mama and Papa had gone to their bedroom, leaving the kitchen table where words that Lena didn’t understand were often spoken—words like foreclosure, default, and moneylenders that she’d never seen on the pages of the Bible that was her schoolbook.

When Lena knew what a word meant, she could release it from the captivity of her thoughts. The words are secrets, she thought. These are words that her parents spoke to each other but didn’t want Lena to know. These troubling words that she heard Mama and Papa speak every night after she went to bed—when they thought she was asleep in her little room off the kitchen—could not be liberated. They assailed her all day and night, like the grasshoppers that had ruined last year’s wheat crop when they emerged like a plague out of the Book of Exodus, darkening the July sky as if they had devoured the sun along with everything else in their path.

These words left no traces, no broken stalks of wheat and corn in what had been a verdant garden. Yet they seemed to be more frightening than that terrible time when the grasshoppers were outside and inside, a hideous, buzzing army from which there was no escape. These words were not even visible, and yet Lena sensed that her parents were afraid. When she was with them, those words were never uttered. Sometimes, when she came into the kitchen where they were talking, the words stopped. But she didn’t know why, and she couldn’t ask.

It was the first time she became familiar with fear, the time of the grasshoppers. Until then, their Nebraska farm, their good-hearted, hard-working neighbors, and the affection of her parents had welcomed Lena into a world where joy was as familiar as the frankfurters, pretzels, and potato salad that Mama served her family, or Papa’s open arms when she ran to greet him as he came into the sod house after the day’s work was done.

Now, there were no voices coming from the room where her parents slept. Lena nestled down into her straw mattress and pulled the sheet over her body. She could sleep now. Maybe tomorrow, the words would leave, the way the grasshoppers had eventually left, and they would all laugh again. It was very dark in the house, but the sod kept the heat of the day at bay, just as it kept them warm in the winter. Dark and cool and comfortable, this house was the only home she remembered. She could, for the duration of the night, surrender her thoughts to slumber and sleep upon the memories of happy days.

Lena awoke not to the gentle trill of Mama calling her or by the rich scent of eggs and sausages cooking over the fire but by a strange, unfamiliar noise that crackled in the silence of the night. The fires were not lit, and yet Lena smelled flames all the same. Heat wafted down upon her from above, slithering through the chinks in the roof. Lena could not understand why the night had suddenly gotten warm, and she scrambled out of her bed, her braided brown hair mussed from sleep, her white nightgown an unlikely source of illumination in the dark room.

Suddenly, a piece of the roof fell in front of her, flying from above as if flaming wings carried it. She cried out in alarm.

“Lena, go outside!” Papa’s voice, struggling to be heard over the sounds of the crackling flames, suddenly tore through the darkness from her parents’ bedroom. “Run!” But if his voice came from inside, why would Papa tell her to go outside? “Run, Lena, run!” then she heard a gunshot, and his voice fell silent. Then, a scream from inside. Another gunshot.

The smoke was oppressive now, choking the hole left by the fallen piece of the roof. Lena grabbed her sturdy-soled shoes and Mama’s Bible and ran out the door.

Outside, the scene that met her eyes was even stranger. Figures on horseback moved behind the thick gray smoke as if they were active behind a veil. They shouted words that she didn’t understand, their voices simultaneously angry and triumphant.

Then, a man with a torch moved out from the veil. He looked down at her. Lena looked up at him. The flame from the torch illuminated his face, leaving the rest of his body in darkness so that his head appeared to be without a body, bobbing against the smoke.

He had a cruel face, and a vicious scar slashed across his cheekbone. His hair was dark but gleamed under the menacing halo of the torchlight as if he were a disembodied demon like the ones that Jesus drove out of the sick people He saved. She watched as his lips stretched out across his face, making the scar on his cheek move as well.

Another figure emerged from the curtain of smoke. “Deuce,” the man spoke urgently, “what do we do about the girl?”

The head that belonged to the one called Deuce glanced down at her, their eyes meeting.

“Leave her. She’s just a kid. She won’t cause any trouble.”

The head turned away and went back behind the curtain. Fixed to the spot where she stood, Lena could only stare. The noises of men and horses retreated, leaving only the crackling sound of the flames devouring the little sod home.

***

Lena knew what bullets were but didn’t know what murder was. She asked Mrs. Olafsen, who was too old and frail to help with the mysterious tasks that needed attending. But she could spend time with a silent little girl and try to urge her to eat something, to drink, to cry if she needed to. She stood at Lena’s side as the coffins holding the bodies of Mama and Papa were lowered into the ground. Mrs. Olafsen held her hand as Reverend Kreider said more words—words like dust and returneth. They were words Lena knew and could even read, but she did not understand what they had to do with Mama and Papa.

She hadn’t seen Mama and Papa before they were put into the wooden coffins for burial. Mrs. Olafsen said it was better that way. Lena didn’t know why, and no one would explain. The women of Goshen did not often show emotion, but some of the women had tears in their eyes as they looked away from Lena. They didn’t explain why they looked away. Lena wondered if she wasn’t supposed to be alive when her parents were dead. She didn’t know if she wanted to be alive without them. Everyone was very kind, but they didn’t understand what she herself struggled to comprehend.

The Olafsens took her home to stay with them while “matters were sorted out.” This was something else Lena didn’t understand, but she went in the wagon with Mr. and Mrs. Olafsen, old Mrs. Olafsen, Emil, Katrina, Klaus, and the baby, Dieter. She knew them all from when she had walked to their house to have lessons with old Mrs. Olafsen. Back then, they had all laughed and played.

Lena didn’t want to play now. She didn’t think she’d ever want to play again. She held onto Mama’s Bible and would not put it down except when it was time to wash.

“Your uncle will be coming for you,” Mrs. Olafsen told her a few days after her parents had been put into the ground.

Lena didn’t know she had an uncle. Mama and Papa had not spoken of him.

“He’s coming from Colorado. He has a ranch there. He’ll take you to live with him.”

Lena wondered where Colorado was. She didn’t think she wanted to go to live with an uncle she didn’t know, but she didn’t say this.

“He’s your father’s brother,” Mrs. Olafsen went on. They sat outside. The Olafsen children went about their morning chores on the farm. Lena could hear their happy voices calling to one another in the sunshine. She used to like to play in the sunshine. She didn’t know why she didn’t like playing anymore. The brightness hurt her eyes now.

“Half-brother,” Old Mrs. Olafsen corrected.

“Yes, half-brother,” Mrs. Olafsen amended. Her hands rested over the potatoes she had been peeling. Mrs. Olafsen liked to do her kitchen work outside because the sod houses were so dark inside.

What is a half-brother, Lena wondered. Which half would it be? Would it be like the man named Deuce, who had only seemed to have a head?

“Your father’s mother was a widow,” Mrs. Olafsen explained, sounding as if she didn’t quite know what to say. “When your father’s father died, she remarried. She and her new husband had a son. His name is Eric Sandor. He’s your Uncle Eric. He’s your family now. It’s right for children to grow up with family. He’ll take care of you.”

***

“Get in the wagon!”

Lena looked to Mr. Olafsen, who lifted her up in response to the harsh order. Mr. Olafsen looked displeased, and he patted her hand after he put her into the wagon. His weather-beaten features looked troubled. Lena thought that Mr. Olafsen didn’t like her uncle. She didn’t know if she was going to like her uncle either.

“In the back!” the man sitting in the wagon seat barked. He gripped the reins in his thick, big-knuckled fingers as if he had no wish to waste any time in leaving. Papa’s hands had been rough and calloused, but they didn’t look like these. Maybe that was how it was with half-brothers. “I don’t need no kid up here getting in my way. Those her things?”

“There wasn’t much left from the fire,” Mrs. Olafsen explained, her tone apologetic, as she picked up the small parcel wrapped in string and put it in the back of the wagon beside Lena.

Lena had been wearing clothes that belonged to the Olafsen daughters. She knew that the parcel contained those clothes. Mama’s Bible was also in the parcel. Lena wasn’t sure why, but she was glad that her uncle didn’t know about the Bible.

This man, Lena realized, was the uncle who was going to take her away to live with him. He grimaced. Lena was relieved to see that he was a whole person, not a half. But he didn’t look anything like Papa, who had thick brown hair, a neat beard, and smiling gray eyes like a kindly Old Testament prophet. The half-brother had a big, bushy beard that reminded Lena of an overgrown garden when winter ended and spring began. He had more hair growing out of his face and chin than he had on his head, which seemed very strange to Lena. He had combed his light brown hair toward his forehead instead of back from it, and she could glimpse bits of his scalp amidst the straggly strands. Although he was the only person sitting on the wagon seat, he took up so much of the space that Lena doubted there would have been room for her. When she had gone in the wagon with Mama and Papa, they had all fit snugly in the seat.

“Nothin’ for her keep, I don’t reckon,” he grumbled, giving the Olafsens a suspicious scrutiny as if he thought they might have been hiding money from him.

“Nothing,” Mr. Olafsen, tall and broad-shouldered, his face unusually rigid as he replied. “The fire took almost everything.”

“What about the livestock?” Uncle Eric demanded with his lower lip thrust out belligerently. “You telling me the barn was set afire too?”

Mr. Olafsen’s face grew rigid, and he spat out his words in his mouth like they tasted bad while his eyes remained fixed on her uncle. “The rustlers took everything else,” he said. “They set the house on fire, they shot the Tasses, and they took the animals. Don’t you—”

His wife put a hand on his arm. Mr. Olafsen stopped talking.

“Mr. Sandor,” Mrs. Olafsen interjected, squinting from beneath the brim of her straw hat as she spoke to him. “The child is a good girl. This has been hard on her, to lose her parents and her home. You will…you will take care of her?”

She sounded as if she were pleading with the half-brother to do something she doubted he was able to do, Lena thought.

“She’ll have a roof over her head,” the gruff man replied. “She’ll earn her keep.”

Without another word, he slapped the reins hard against the horse’s haunches. The horse immediately began to move at a swift pace. Lena, not prepared for the movement, fell against the side of the wagon. Mrs. Olafsen left her husband’s side as if she wanted to hurry to help Lena regain her balance.

Lena steadied herself against the wagon side. She stretched her legs out on either side of the parcel and gripped it.

Mrs. Olafsen was leaning against Mr. Olafsen’s chest as if she might be crying. She watched as the Olafsen children clustered close to their parents. They still had a family. She had a half-uncle who talked with a loud voice and had big, hard hands. But Lena knew that her father’s half-brother wasn’t going to be a family.

Chapter One

Durango, Colorado

April 1880

“You sit there, girl, right at the end of the drive, you hear me?”

Uncle Eric put on his hat, then turned to glare at her, one hand on the doorknob. “I expect you to sit there, just like I tell you, till I come home. You hear me?”

The conversation was the same every Saturday night in the three years since she’d arrived in Colorado to live with her uncle. But there were variations, such as tonight, when she’d been taking the laundry off the line and hadn’t had time to clear the table after the evening meal. “The supper dishes?”

Lena kept her words to a minimum, knowing how impatient her uncle became when she took too long to answer him. But they’d finished supper, and she wanted to clear the table. Uncle Eric didn’t like it when she left her chores undone.

By way of an answer, her uncle cuffed her across the face. She stumbled back, stabilized by the wooden table with the remains of the supper she had cooked still on it. “Don’t sass me, girl, I’m tired of you sassing me. When I tell you to sit there and wait for me, that’s what I mean. You too stupid to understand?”

Lena feared that she was stupid. Mama and Papa had not told her that she was stupid, but she must always have been, and they were too kind to point this out to her. Uncle Eric constantly had to tell her what to do, and she always did it wrong, earning herself a blow or a slap for her error. Always fearful that her clumsiness and stupidity would lead to blows, Lena opted to speak as little as possible. She simply nodded, then shook her head, confused at what remark she was answering.

She didn’t fall back this time when Uncle Eric’s hard palm found her cheek. She stood where she was against the table, taking the slap. She didn’t cry out or put her hand to her stinging cheek, knowing that would only bring on more blows.

“All right then,” he said. “You bring the chair along and follow me. I want to see you sitting down on it before I leave.”

She picked up one of the heavy wooden chairs that framed the kitchen table, struggling slightly to hold it as she followed her uncle down the four wooden stairs, each one in varying need of some repair, leading away from the squat ranch house where she had lived for the past three years.

Uncle Eric waited impatiently at the bottom. “Get a move on girl,” he shouted. “Waitin’ on you, all the whiskey in the saloon will be gone before I get there.”

She stumbled slightly on the last stair, where the plank was starting to split in half. Uncle Eric’s beard split across the lower half of his face as his lips curled in a downward semicircle of disdain. “Clumsiest girl in Colorado, that’s you, girl,” he growled.

He aimed a hand at her shoulder but missed. “Stupid girl,” he muttered, then continued walking to the end of the path where his horse, saddled and tethered, waited, although Juan, the ranch hand who had brought him, was nowhere to be seen.

“Where the devil is that lazy bandito?” Uncle Eric complained.

“He goes to mass,” Lena ventured. Juan was not a bandito, but it amused her uncle to refer to the Mexican man with such a slur. She knew that Juan Arguedas, the man who did the work of a foreman in exchange for what she knew was the pay of a hired hand, took his family to church in the evening because the local priest traveled to a wide itinerary of parishes to lead the mass.

“I don’t pay him to prance off to sit on his lazy backside doing nothing,” Uncle Eric complained. “Wait until I see him next time. I’ll teach him to short me hours.”

Lena wasn’t particularly worried about the threat to Juan. She knew that when her uncle returned home from the saloon, he would have no recollection of anything that had happened in the hours before he had his first whiskey of the night.

“Right here,” Uncle Eric said, pointing to the spot where she was to sit and wait for her uncle to arrive home. She sat there every Saturday night, waiting, but her uncle repeated the instructions weekly. To her right was a broken wagon wheel that Uncle Eric said he would fix but hadn’t touched in the three years since one of the spokes cracked. To the right was a patch of blue columbines struggling to thrive in the midst of an overgrowth of their withered predecessors. Straight ahead was the undulating road that led from the ranch to the saloon.

Uncle Eric mounted Soldier. Leaning down from the saddle, he waggled a warning finger at his niece. “You sit right there,” he ordered. “I don’t care how late it is. I don’t care how dark. You sit here and you wait till I get home so you can help me inside. You hear me?”

Lena nodded.

“You hear me? Answer me when I ask a question. Don’t give me that fool bouncing of your head, I want to hear you say it.”

“I hear you.”

He nodded in satisfaction, dug the toes of his boots into Soldier’s sides, and the horse responded.

Lena watched as the figure of her uncle and Soldier receded as the road took them through the jagged peaks of the mountains on either side of the road. She waited until they were no longer in view, and all she could see ahead was the broad expanse of sky, still bright with light on this early spring day, and the mountains, broad like the shoulders of a giant, big enough to challenge the sky for space.

She remembered the flat, treeless fields of Nebraska, where the endless tableaux of wheat swayed in the breezes as if they were bowing to honor the majesty of God in His heavens. She’d been in Colorado for three years and sometimes felt as if Colorado’s terrain defied God. The enormous, clawing hands of the mountain peaks, like the towers of Babel in the Bible, looked like they were endlessly striving to reach God’s celestial kingdom and overpower His domain.

Perhaps it was not Colorado, but her unbelieving uncle who made her think this way, Lena realized. She waited longer. She knew Uncle Eric was gone now, as he was every Saturday night. He would drink his fill until he returned, sprawled across his saddle, depending on Soldier to get him back to the ranch, and then relying on Lena to help him into the house and onto his bed. There, he would lay in his drunken stupor until at least noon the following day. Lena was forbidden to attend church. Her duty, Uncle Eric had made clear, was to tend to him in his bleary-eyed, whiskey-sodden, foul-tempered state until he was able to stand upright on his own.

Lena put her hand on the pocket of her apron and rested it upon the contents inside, well hidden from Uncle Eric’s view. It was Mama’s Bible, and on these Saturday nights, after she could be confident that her uncle was well on his way to the saloon, she took the Bible from her pocket and continued to teach herself to read.

Uncle Eric had no patience with Bible reading and saw no reason why a woman even needed to know how to read. She had learned his views on the Bible very early upon her arrival at his ranch when, after preparing the meal, she had bowed her head, waiting for him to give the blessing. A thundering fist had pounded against her head, knocking her to the floor. “I’ll sew your mouth shut,” he’d warned, towering over her with his upraised fist ready to repeat the blow that had sent her reeling, “if you ever bring your prayer-prattling ways to my table again! You hear me, girl?”

She had nodded in fright.

“You hear me? Don’t bob that head of yours or I’ll knock it sideways.”

“I hear you.”

Lena had never folded her hands in prayer at the table again. Yet she had never forgotten to pray. In the years since she had become the charge of her uncle, Lena had learned to live in silence where fear made the rules, and faith figured a way around them. She prayed without words as she stirred the soup over the fire and thought of Bible verses in her head as she rolled out dough on the table. Every chore that fell to her to do during her busy day was accompanied by the well-remembered scripture with which she had been raised, and every task began with an unspoken prayer of entreaty to God.

With her uncle away for hours and only the sky to witness her infraction of her uncle’s edicts, Lena led her own worship for a congregation of one. She inhaled the sweet hints of spring in the air. “‘I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help,’” she recited, hearing old Mrs. Olafsen’s voice in her ears.

This was her time, free of her uncle’s abuse, when she could worship freely without fear of being reprimanded or scoffed at or, not infrequently, slapped for making a reference to God. She bent her head over the Bible. She struggled with words that were unfamiliar, sounding them out again and again until the letters somehow made sense to her. It didn’t always work, but it was the one time during the week when she could honor God with her worship and honor her parents by continuing the reading lessons that had meant so much to them. In these solitary hours, Lena allowed happy memories to return to her so that, albeit briefly, she had her family again.

Despite her fears of her uncle discovering her reading her Bible, she was not alarmed when she heard the sound of footsteps upon the meandering path that led to the entrance of the ranch.

“Hola, Juan,” she greeted without turning around.

She heard a warm chuckle, and she smiled in response Juan wasn’t a family member, but he was good-hearted and kind, and he never made her feel stupid. “Hola, mija.”

She was not Juan Arguedas’ daughter, of course. He had two daughters, two sons, and a wife to whom he was devoted. But he was kind when her uncle was harsh, encouraging when Uncle Eric was derisive, and patient at all times, which was not a trait that she had ever seen in her uncle’s behavior. Sometimes, during the inevitable bursts of temper before he left on his Saturday night drinking, Juan positioned himself between her and her uncle’s fists when Uncle Eric’s tirade turned violent. It was entirely through God’s providence and her uncle’s inebriation that Uncle Eric forgot that the vigilant foreman had protected Lena.

“Querida, he will not return for some hours yet,” Juan said, approaching her chair and kneeling beside it so that his gaze was level with hers. “Go inside,” he coaxed. “He will not know and you ought not to sit out here waiting so long.”

Lena shook her head so vigorously that her long, chocolate-brown braid twisted with the effort. “I have to stay,” she said. “He said to.”

The foreman sighed and looked past her to the road winding between the mountain range divided by its path. “Lena,” he said, his leathery tan face devoid of its usual smile. “This is not good for you.”

“I have to stay here, Juan,” she repeated. “You know…you know what he’ll do if I’m not here.” Her gray-blue eyes, a gentle blend of sky and cloud that had been taken directly from the heavens, met his gaze with the heart-wrenching torment of a storm that had nowhere to burst.

Juan sighed again. “This is not good for you,” he repeated. “He will be at the Painted Lady until he can no longer sit on the bar stool. Then Señor Whitacre will put him back on Soldier and Soldier will bring your uncle home. You will wait out here in the dark and you will help him to get inside and put him to bed because he will be too drunk to manage on his own.”

Juan’s kindness touched her. She knew better than to expect such things from her uncle. “It’s the way things are.”

“You will not always be a child,” Juan said, suddenly turning serious. “One day, you will marry. Perhaps a good-looking young man with a heart that belongs to God. Milagro thinks I am the handsomest man she has ever seen!” he laughed as if his wife’s fancy was quite amusing. “If you marry one day, when you are old enough, you could escape. A husband, a good man, he could take you away from this. You need to be thinking of that. Remember, the heart that belongs to God first is the heart that will be loving to you.”

But they both knew it was a forlorn hope. She was only twelve now, and marriage seemed very far off in an uncharted distance. She was trapped on the ranch. She was forbidden to attend church, and so activities of the people of Durango were denied to her. She clung to the comforts of scripture, and she looked to the hills, from whence her help would come. There was no sign of it yet. God would not fail her. But God’s time, old Mrs. Olafsen had told her, was not our time. In the meantime, she, like the Hebrew slaves in Egypt, must continue to make bricks without straw.

“There must be a way, mija,” he said, standing up, wincing as he did so. At the age of forty-five, Juan had been a ranch hand all his life, and his body told the tale of the falls he had taken from horses, the injuries sustained in a cattle stampede, and the daily exertion of work that afforded him little rest.

There wasn’t a way. Lena already knew that, and Juan knew it too. The difference was that she had accepted her fate.

Juan had not.

Next chapter ...

You just read the first chapters of "A Faithful Bride for His Broken Heart"!

Are you ready, for an emotional roller-coaster, filled with drama and excitement?

If yes, just click this button to find how the story ends!

I enjoyed the preview.

So glad to hear this!💗

This book sounds exciting. Can’t wait to see Lena leave her uncle alone with his whiskey and demons. I’m hoping she will find a man of faith to live and care for her.

Thank you so much!💗💗

I am looking forward to reading this book.

Hope you enjoyed the book!💗💗